The stunning John Hopkins Glacier.

July 30, 2017

Today was a very special day on the Volendam. We were going to explore Glacier Bay. This was our second time here in four years and I was excited. The park was named a national monument by President Calvin Coolidge in 1925. In 1980, Jimmy Carter increased its acreage and elevated its status to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The park encompasses 3.3 million acres and Glacier Bay lies in the middle of the huge preserve. Its many inlets and fjords contain sixteen active tidewater glaciers fueled by enough snow to flow out of the mountains and down to the sea.

Rodge and I awoke at 6 a.m. so that we could get dressed and eat in time to take in the full day. At 7 a.m. we entered Glacier Bay and picked up two park rangers at Bartlett Cove (Park Headquarters). They spent the day as our guides and provided informative commentary as we cruised throughout Glacier Bay.

The captain opened up two levels of the bow of the ship so we could have a sweeping view of the bay. It was cold and breezy there so we were all bundled up in our parkas and hats. Along with a warming sun, there was a coffee and hot chocolate station set up on deck to help take the chill off.

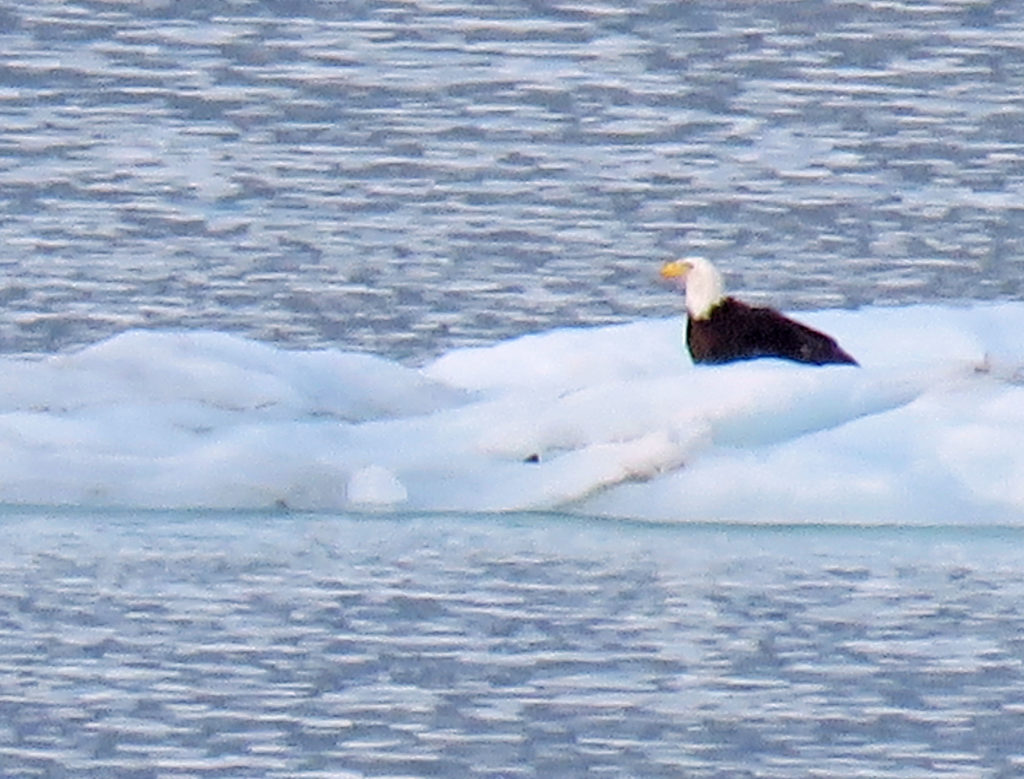

As we glided through the green-blue waters of Glacier Bay, the reflection of the ice-capped mountains in the still water lent an air of solitude and tranquility to our visit. We saw wildlife all around us. Humpback whales waved to us with their tails as they dove in and out of the water. Dall sheep grazed on the top of mountain ridges. High-soaring bald eagles glided through the air scanning for prey. At one point, I saw a bald eagle float by on an iceberg.

As we slowly made our way fifty-five miles north to the tidewater glacier faces, Park Service Rangers in the ship’s bridge provided audio narration of what we were seeing. They pointed out features of interest and a wide variety of wildlife (bald eagles, otters, whales, Dall sheep etc.). The glaciers we cruised by are called tidewater glaciers because they end in the water and break off into icebergs.

At mile 40, we arrived at Reid Glacier. The 9.5-mile-long, .75-mile-wide glacier was named by members of the 1899 Harriman Alaskan Expedition for Harry Fielding Reid. Reid Glacier is one of the few glaciers that can be accessed from shore. A mile later, we entered stunning John Hopkins Inlet, a nine-mile path bounded by steep, ice-carved walls that reach more than 6,000 feet skyward on either side. At the mouth of the inlet is the Lamplugh Glacier, one of the bluest glaciers in the park. It is 16 miles long and .75 miles wide. It is known for its huge subglacial river and cave that appears each summer.

But the crown jewel of the inlet lies at the very end, the John Hopkins Glacier. The glacier was named after John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland by Harry Fielding Reid in 1893. It is one of the few advancing tidewater glaciers of the Fairweather Range. The glacier is more than a mile wide and twelve miles long. Its jagged face rises 250 feet from the water. As I looked at the stunning glacier I could see two peaks from the Fairweather range rising above it. The peaks are named Mount Wilbur and Mount Orville, after the Wright brothers.

We left John Hopkins inlet and continued north into Tarr Inlet. It was 11 a.m. and the stewards started serving us Dutch Pea Soup on the foredeck. It was just the thing to warm us up a bit without having to go inside. Soon, we arrived at Margerie Glacier, named for the French geographer and geologist Emmanuel de Margerie who visited Glacier Bay in 1913. Inside the inlet, calm, blue-green waters were dotted with chunks of ice. The massive glacier towered 250 feet above us. The mile-wide ice flow stretched twenty-one miles from the south slope of Mount Root on the Alaska-Canada border to Tarr Inlet.

Our ship slowed and coasted within a quarter-mile of the massive ice face. Passengers lined the bow with binoculars and cameras to capture a view of the towering ice queen. Margerie Glacier with the Fairweather Mountains lurking behind, towered over the water’s surface. The jagged edges left in the top of the glacier from pieces falling away formed intricate shapes and patterns.

The ship spent about a full hour in front of the Margerie Glacier. The captain allowed plenty of time for everyone on board to see the glacier by turning the ship slowly so that all sides faced the glacier for a considerable amount of time. As we crowded the rails, a hush came over the ship. Suddenly, we heard a loud crack, and then a noise that sounded like a thunderclap. The silence was shattered as a chunk of ice crumbled and slowly fell into the water. Margerie Glacier was actively calving or breaking off ice chunks. Compared to glacial ice, seawater is warm and highly erosive. As waves and tides undermines some ice fronts, great blocks of ice up to 200 feet high may calve or break loose and crash into the sea.

Just adjacent to Margerie Glacier is the largest glacier in the park, the Grand Pacific Glacier. Standing 180 feet above the water, it is two miles wide and 34 miles long. At 1 p.m., we left Tarr Inlet and spent the rest of the afternoon cruising south through Glacier Bay. We passed by John Hopkins Inlet again and got another glimpse of the virtual winter wonderland. Hanging glaciers on mountainsides glistened in the afternoon sun. Sparkling icebergs floated by in calm, icy waters. I hated to leave such a magical place.

As we cruised out of Glacier Bay, I was inspired by its rugged, limitless beauty. I was also humbled and in awe of its snow-covered landscapes and icy sculptures. Only God could have created such a masterpiece.

In awe,

Kathy

It’s Sunday on the Volendam!

On the bow of the ship all bundled up in our parkas.

Making our way through blustery Glacier Bay National Park.

Snow covered mountains line the waters of the bay.

Reid Glacier, a 9.5 mile-long glacier that can be accessed from shore.

Rodge enjoying hot chocolate on the forward deck.

Lamplugh Glacier found at the mouth of the John Hopkins Inlet.

The Lamplugh Glacier is one of the bluest glaciers in the park.

Kathy being photobombed by Lamplugh Glacier.

This is an example of the layering effect of a glacier.

Layers of ice and dirt are trapped inside the glacier.

Beautiful ice sculptures formed by years of glacial activity.

A small cruise ship exploring Glacier Bay.

A bald eagle enjoying a morning cruise.

The crown jewel of the inlet lies at the very end, the John Hopkins Glacier.

Two peaks rising above the glacier named Mounts Orville and Wilber.

A bald eagle hitching a ride on a an iceberg.

Margerie Glacier from a distance.

Passengers lined the bow with cameras to capture a view of Margerie glacier.

The jagged edges were left in the top of the glacier from pieces falling away.

Margerie Glacier with the Fairweather Mountains lurking behind.

The mile-wide ice flow stretched 21 miles and towered 250 feet above us.

A retreating glacier.

Another retreating glacier gives way to green grasses.

Another magnificent view of Glacier Bay.

The Grand Pacific Glacier is the largest glacier in the park.

Standing 180 feet above the water it is two miles wide and thirty-four miles long.

Leaving Glacier Bay National Park.

Gentile waves move across the blue-green water.

Kathy relaxing on the deck after a marvelous day in Glacier Bay.